![]()

![]()

Links.

The Relic of Saint Lawrence – Parish Church of Saint Lawrence,

Lancashire Folklore "the bones of St Lawrence" year -1867.

Documentary evidence for -: “the Relic of Saint Lawrence"

Whose Head did Sir Rowland Standish bring from Normandy?

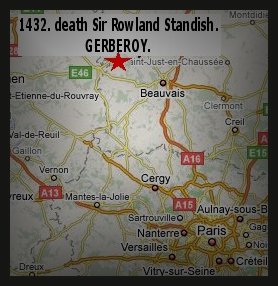

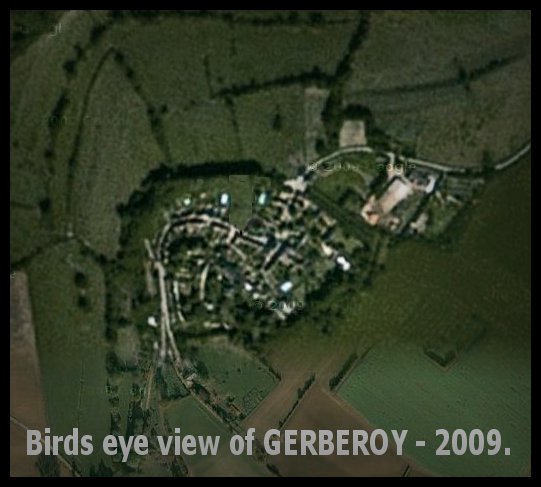

Sir Rowland Standish fought and died alongside John FitzAlan,14th Earl of Arundel near Gerberoy, Normandy,France in the year 1435.

John Fitzalan and Rowland Standish were noblemen of Norman descent.

John Fitzalan was a military commander during the Hundred Years War (the French Civil War). For two years John Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel was a commander in various campaigns in France. In May 1435 he was wounded in the leg in action near Gerberoy. The leg was amputated, but he died a month later.

Mont Saint Michel, Normandy, France.

The Norman French noblemen return from England to defend their homeland of Normandy from the French King.

![]()

The Relic of Saint Lawrence – Parish Church of Saint Lawrence, Chorley, Lancashire, England.

Parish Church of Saint Lawrence, Chorley, Lancashire, England.

Window in the Parish Church of Saint Lawrence, Chorley.

The Parish Church of Saint Lawrence, Chorley, Lancashire, England is dedicated to St. Lawrence deacon of Rome Martyred on a gridiron in the year 258 as the stained glass window in the church depicts.

1498.

In the year 1498 the then lords of the Manor of Chorley,

Sir George Stanley, Lord Strange, and Joan his wife, Sir Edward Stanley,

Knight, and Sir Richard Sherburn, Knight, claimed as such, amongst other

privileges, a fair on the vigil, feast, and morrow of St Lawrence, that

is to say, on the 9th, 10th, and 11th August.

This is in itself a strong proof that St. Lawrence was then

regarded as the patron of Chorley Church: for nearly

all of the country fairs and feasts had their origin in the celebration of the

feast of the patron saint of each particular church.

The annual fair of St. Lawrence has long ceased to exist but it was held as late as the year 1684.

1534.

Albeit the king's Majesty justly and rightfully is and ought to be the supreme head of the Church of England, and so is recognized by the clergy of this realm in their convocations, yet nevertheless, for corroboration and confirmation thereof, and for increase of virtue in Christ's religion within this realm of England, and to repress and extirpate all errors, heresies, and other enormities and abuses heretofore used in the same, be it enacted, by authority of this present Parliament, that the king, our sovereign lord, his heirs and successors, kings of this realm, shall be taken, accepted, and reputed the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England, called Anglicans Ecclesia; and shall have and enjoy, annexed and united to the imperial crown of this realm, as well the title and style thereof, as all honors, dignities, preeminences, jurisdictions, privileges, authorities, immunities, profits, and commodities to the said dignity of the supreme head of the same Church belonging and appertaining; and that our said sovereign lord, his heirs and successors, kings of this realm, shall have full power and authority from time to time to visit, repress, redress, record, order, correct, restrain, and amend all such errors, heresies, abuses, offenses, contempts and enormities, whatsoever they be, which by any manner of spiritual authority or jurisdiction ought or may lawfully be reformed, repressed, ordered, redressed, corrected, restrained, or amended, most to the pleasure of Almighty God, the increase of virtue in Christ's religion, and for the conservation of the peace, unity, and tranquility of this realm; any usage, foreign land, foreign authority, prescription, or any other thing or things to the contrary hereof notwithstanding.

Accordingly, in the summer of 1535, directly after Sir Thomas More's execution, Cromwell, now vice-regent of the king in his ecclesiastical jurisdiction within the realm issued a commission for a general visitation of the religious houses, the universities, and other spiritual corporations. The persons appointed to conduct the inquiry were Doctors Legh, Leyton, and Rice, ecclesiastical lawyers in holy orders, with various subordinates as upright and plain dealing as they were assuredly able and efficient. It is said by some writers that the inquiry was set on foot with a preconceived purpose of spoliation; that the duty of the inquiry was rather to defame roundly than to report truly; and that the object of the commission was merely to justify an act of appropriation, which had been already determined. It has been shown that an inquiry was a plain matter of necessity. It is equally certain that antecedent to the presentation of the inquiry report, an extensive measure of suppression was not evident. The directions to the lawyers, the injunctions which they were to carry with them to the various houses, the private letters to the superiors, which were written by the king and by Cromwell, show plainly that the first object was to reform and not to destroy; and it was only when reformation was found to be conclusively hopeless, that the harder alternative was resolved upon. The report itself is no longer extant. Bonner was directed by Queen Mary to destroy all discoverable copies of it, and his work was fatally well executed. Researchers are able, however, to replace its contents to some extent, out of the dispatches of the commissioners

1535.

Evidence from a visitation provides a small spark of English life in the winter of 1535, lighted by a stray letter from an English gentleman of Cheshire - Sir Piers Dutton.

The Lord Chancellor was informed by Sir Piers Dutton, justice of the peace, "that

laywers of the visitation had been at Norton Abbey. They had concluded their inspection,

had packed up such jewels and plate as they purposed to remove, and were going

away when, the day being late and the weather foul, they changed their minds,

and resolved to spend the night where they were. In the evening the abbot of Norton Abbey gathered together a great company, to the number of two or three hundred persons, so

that the commissioners were in fear of their lives, and were fain to take a

tower there; and there from sent a letter unto me, ascertaining me what danger

they were in and desiring me to come and assist them, or they were never likely to come thence. Their letter came to me about

nine of the clock, and about two o'clock on the same night I came thither with

such of my tenants as I had near about me, and found divers fires made, as well

within the gates as without and the said abbot had caused an ox to be killed,

with other victuals, and prepared for such of his company as he had there. I

used some policy, and came suddenly upon them. Some of them took to the pools

and water, and it was so dark that I could not find them. Howbeit I took the

abbot and three of his canons, and brought them to the King's castle of Hatton". - Sir Piers Dutton, justice of the peace.

1548.

In the year 1548 Sir Rogerus Chorley was a priest at Chorley when the commissioners came to undertake their duties of inspection. In Chorley they must have been disappointed. They found 'three vestments only, three albs and but one chalice, one candlestick, two altar clothes, two cruets of pewter, one broken censer, two towels and a Bible.The valuable silver had no doubt been removed by the families who had given it. Perhaps the skull of St. Laurence returned to the Standishes in this way and this explains why the bones now appear to be from a limb rather than a skull. - George Bertill.

Sir Rogerus Chorley was still priest at Chorley during Mary

Tudor's reign when the country became papist again. He continued to minister

when Queen Elizabeth succeeded her sister and there was change again and

another prayer book — the third. - George Bertill.

The priest who succeeded Sir Rogerus may also have been a

member of a well-known local family. He was Henry Crosse, whose name was the

same as the family at Crosse Hall. - George Bertill.

This family like most other local landed families, were

recusants. Robert Charnock, who is reputed to have built Astley Hall, was

outlawed for an unspecified reason and his brother John was hanged drawn and

quartered for his part in the Babington Plot to assasinate Queen Elizabeth in 1586. - George Bertill.

1552.

In the year 1552, the commissioners came again, and found

again Sir Rogerus Chorley as priest.

This time the commissioners came to confiscate 'idolatrous ornaments and attire' which meant in practice that they sold it on behalf of the crown. - George Bertill.

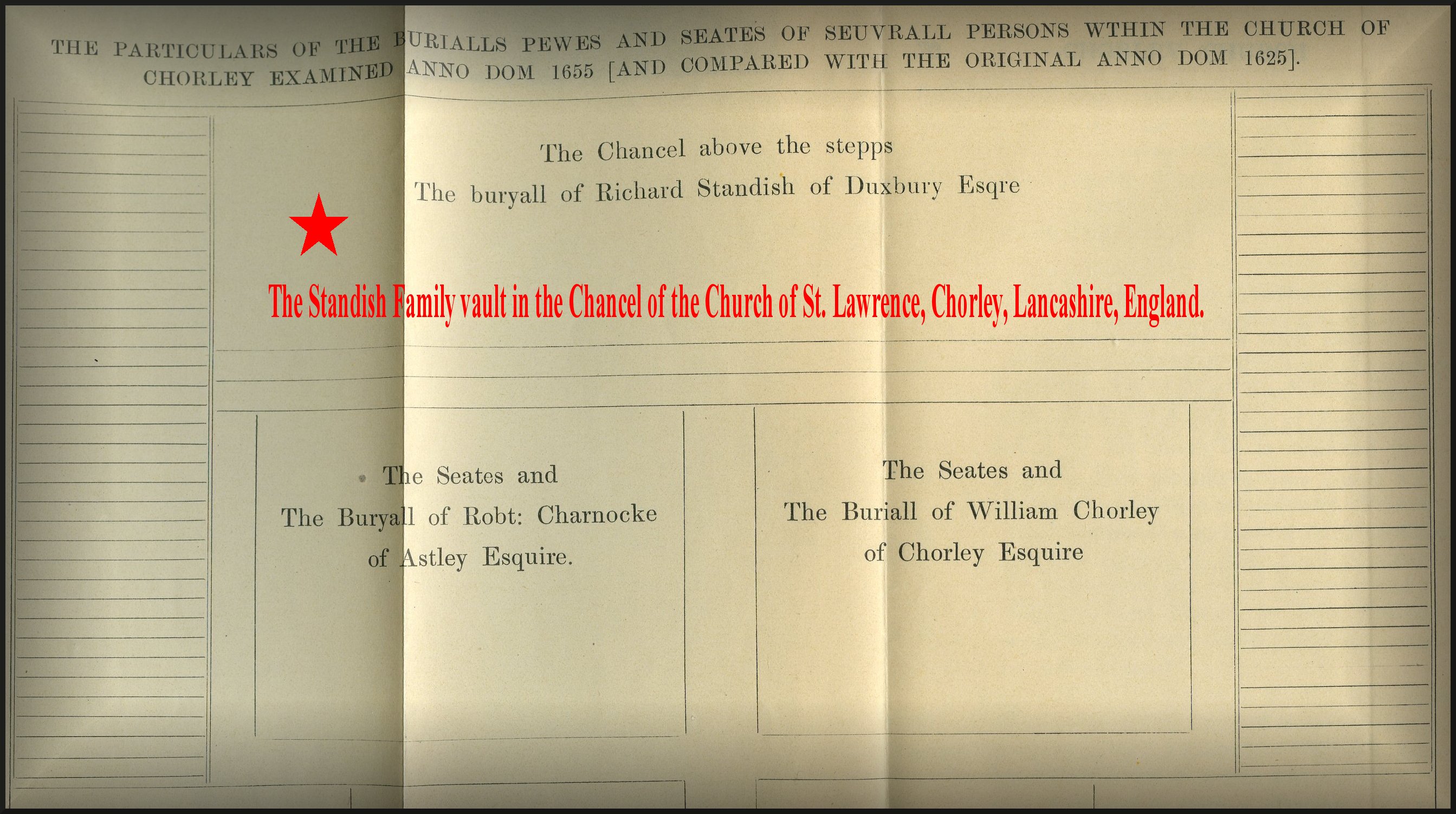

The Standish family burial vault is in the chancel beneath the alter of the Parish Church of Saint Lawrence as depicted on the Church plan drawn up in the years 1625 and 1655.

The Church of Chorley Plan date 1655.

The last person to be buried in the vault was Frank Hall Standish in the year 1841.

The Standish family vault has remained sealed from 1841.

Other notable members of the Standish family (amongst many) buried in the vault are -:

1. 1566. James Standish Lord of the Manor of

Duxbury and his wife Elizabeth Butler from who descend the Irish and Canadian

family branches.

2. 1571. Lawrence Standish of the Burgh upon the Manor of Duxbury and his wife Elizabeth Standish (cousin) grandson of Sir Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1468 – 1507.

3. 1622. Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Duxbury and his wife Alice

the first Puritan members of the Standish family. Alexander made out the

1613 Visitation pedigree given to Richard St. George stating the descent of Sir

Rowland Standish and quoting the contents of the Standish family receipt for

the head of St. Lawrence.

1642. The head of St. Lawrence interred along with Thomas Standish (September 30th.1642) and his father Thomas Standish M.P Lord of the Manor of Duxbury (October 29th.1642) within the Standish Family Vault.

1662.

Then came the Act of Uniformity (1662), whereby ministers

had to swear to conduct worship only according to the prayer book and thus

minister Mr. Welch had to go. He is supposed to have started a Presbyterian

Chapel up the road (now the site of the Unitarian Chapel) on land given him by

William Chorley, who was a non-Catholic.

Mr. Welch had been a good minister for 34 years and some no

doubt remembered how he attended the sick in the terrible plague of 1631 when

the register showed 130 townsfolk died. Perhaps this was why he was not given

away despite notorious legislation including the Five Mile Act, which forbade a

silenced minister to preach within five miles of a town or a parish, where he

had been minister.

In the years that followed Chorley was divided by rival

causes. Jacobite John Crosse whose initials are on a pew at the front of the

church, is supposed to have died as a soldier in the 1688 rebellion, which was

planned as a diversion to get William of Orange on the throne.On the other side were the Standishes of the Pele upon the Manor of Duxbury who were Puritan, as a result of the

influence of Alice, daughter of Sir Ralph Assheton of Whalley Abbey, who

married Alexander Standish in 1592. Whilst most of the neighbouring gentry, including their Standish cousins at the Burgh upon the Manor of Duxbury were Catholic. - George Bertill.

![]()

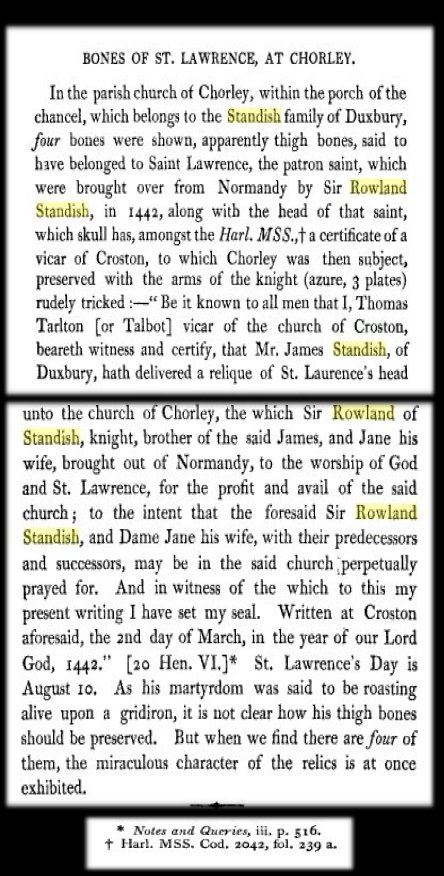

Lancashire Folklore "the bones of St Lawrence" year -1867.

Lancashire Folk lore by John Harland F.S.A and T. T. Wilkinson F.S.A.S published in January 1867 records the popular belief handed down by many generations regarding the relict of St. Lawrence.

![]()

The documentary evidence for -:

“the Relic of Saint Lawrence” at the Parish Church of Saint Lawrence, Chorley.

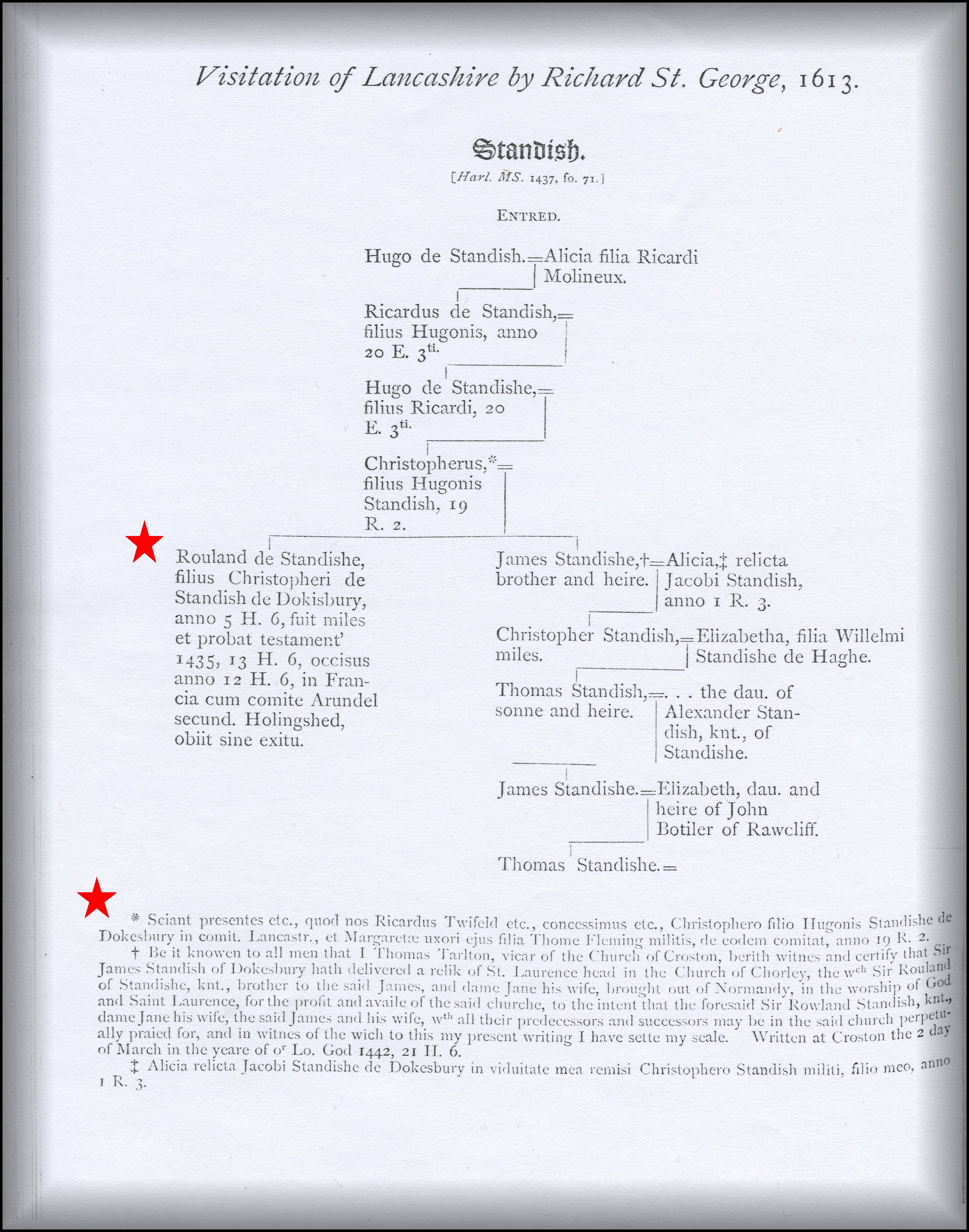

1. The 1613 Visitation pedigree given to

Richard St. George by Alexander Standish, Lord of the Manor of Duxbury.

1613. Richard St. George carried out the

Visitations of the Noble families of Lancashire on behalf of the Crown.

The 1613 visitation report sworn by the Alexander Standish

(Lord of the Manor of Duxbury 1599 – 1622) to Richard St. George was totally

directed at the descent of Sir Rowland Standish Knight, his position in the

family tree and his valiant deeds in Normandy.The visitation report clearly records that the relic of St.

Lawrence had been brought out of Normandy by Sir Rowland Standish and a full word for

word transcript of the receipt of Rector Thomas Tarleton dated 2nd

day of March 1442 made out to the Standish family was incorporated within the

1613 visitation report.

The 1613 visitation sworn by Alexander Standish indicates that the relic of St. Lawrence was still within the Chorley Church and that it was the personal property of the House of Standish not of the church, thus providing the relic with some protection from the agents of the Crown. The actions of Alexander Standish in 1613 also indicate his concern that the relic of St. Lawrence was under threat, but it would be his grandson Alexander Standish in the year 1642 who would take the final action to protect the relic of St. Lawrence.

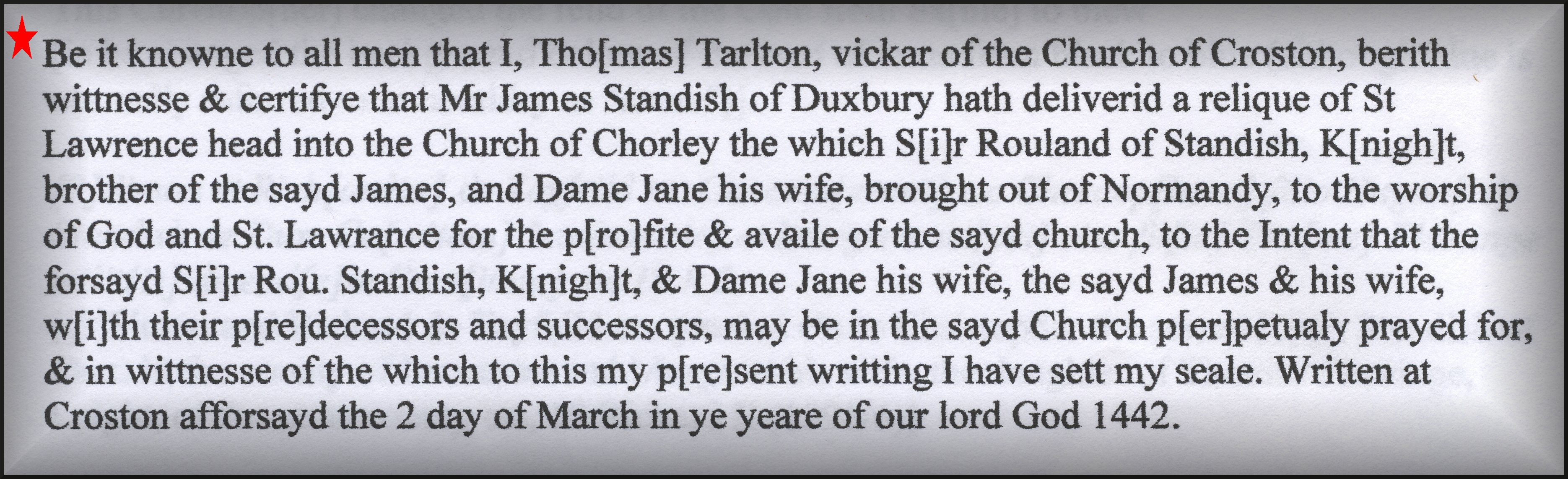

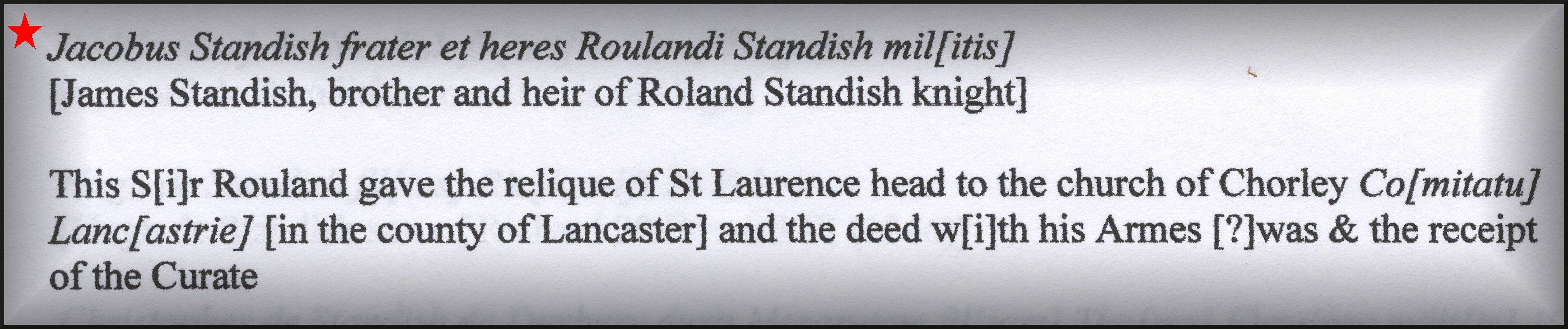

2. 1442. The receipt of Thomas Tarlton Vicar given to James Standish (brother of Sir Rowland) for the head of St. Lawrence.

The receipt of Thomas Tarlton Vicar for the Head of St. Lawrence - British Museum Harl. MSS. Cod. 2042, Fo. 239.

1442. James Standish brother and heir of Rowland Standish gave the relic of the Head of St. Lawrence to the Rector of Croston for the keeping of the relic at the Chorley Chapel known as St. Lawrence. Rector Thomas Tarleton recorded the gift in the Church records and also gave a written receipt to James Standish to confirm that he had complied with his brother Rowland’s instructions to deposit the relic of St. Lawrence at the Chorley Chapel. The receipt of Rector Thomas Tarleton dated 2nd day of March in the year of our Lord God 1442 can be found in the British Museum Harl. MSS, Cod. 2042, Fo. 239. The head of St. Lawrence was brought back to Duxbury several years before the death of Rowland in 1435.It was kept in the Pele Tower of Duxbury the home of the Standish Family until being gifted to the Church in 1442.

3. A copy from an ancient record in the British Library referring to the gift of the head of St.Laurence by Sir Rowland Standish and also two boxes containing -

1. The head of St. Lawrence.

2. Artefacts of Sir Rowland returned from Normandy after his death at Gerberoy France in 1435.

"We are told that the relics of St. Lawrence still preserved in the church, before their installation in their present resting-place, were kept in a box or small chest within the Standish pew." -: Mr. Barritt - Dr. Ferriar. December 1791.

1613. The Church Pew of Alexander Standish, Lord of the Manor of Duxbury.

1540- 1642. The Crown gave many reasons for the need for the Church visitations that saw much of the Church and Abby property sequestered. Relics of the saints were not in general part of the sequestrations unless a value could be attributed to the relic. However to protect the relic of St. Lawrence from being included as the property of the Chorley Church the Standish family kept the head of the saint in one of two boxes within the Standish Pew (the sitting place of the House of Standish within the Church of Chorley) thus making the relic House of Standish property. The second box contained private artefacts of Sir Rowland Standish brought back from Normandy France after his death near Gerberoy in 1435.

1642.

Lancashire Folklore.

Alexander Standish was the last Male of the direct line from Hugh de Haydock - de Standish (1270-1326) and he was also the grandson of Alexander Standish whose sworn statement was recorded in the 1613 Visitation of the Noble families of Lancashire. Aleander suddenly found himself in the unexpected position of “Lord of the Manor of Duxbury”. His elder brother Thomas Standish had been killed fighting in the English Civil War in the City of Manchester 30th September 1642, his father Thomas Standish a member of parliament died just four weeks later on the 29thOctober 1642.

Alexander Standish the new Lord of the Manor of Duxbury was also a Colonel in the Kings Army during the English Civil War, which would result in his own death on the 10th April 1644. The Duxbury estates inherited by Alexander were heavily in debt as a result of the Civil War and in the period between his fathers death in October 1642 and his own death in April 1644 he took several steps to protect the Duxbury estate and family property. One of Alexander’s first actions was regarding the relic of St. Lawrence the lawful property of the Standish family, which Alexander reputedly ordered to be buried in the family vault alongside his brother and father in October 1642. Alexander as a Colonel of the Kings Army was fully aware that the Puritan faith in general considered such relicts to be idolatrous and thus the relic of St. Laurence was at risk in the event that Cromwell was victorious. Alexander also took steps to contain the spiralling debts of the Duxbury estates and as he had no male heir he left the entire Duxbury estates upon his death to his wife Margaret.

1.We are told that the relics of St. Lawrence still preserved in the church, before their installation in their present resting-place, were kept in a box or small chest within the Standish " pew." - Mr. Barritt - Dr. Ferriar. December 1791.

2.These large bones, as Mr. Brownbill observes," are not part of a head, and their origin is quite unknown." He adds: "The original relics would be destroyed at the Reformation, and had they escaped then it is impossible to suppose that strict Puritans like Hyett the rector and Welch the curate would have tolerated them during their long tenure of office."

3.The original relic there was but one may not have been destroyed, but, like others we know of, concealed in a place of safety, to await the advent of happier days; perhaps it was given back to the then head of the donor's family — the Standish family of Duxbury. - Mr. Brownbill (1911)

1642 – 1699. Acts of vandalism were enacted by Cromwell's hirelings in the mid-seventeenth century, with the smashing of the church of Chorley's stained glass and statues; again, had the bones of St Laurence been available, with all their Papist connections, no doubt these too would have suffered a similar fate. - Edwin Fisher.

The English Civil War ended in 1647 and Oliver Cromwell and the commonwealth reigned to 1658 when King Charles the second was reinstated as King. When Charles II was proclaimed King on May 29th 1660, there was much rejoicing with bonfires and the ringing of bells. The maypole reappeared on the town green in Chorley with a crown on top. Unfortunately, it was struck by lightning and split to the ground, a happening which the remaining Puritans did not hesitate to identify as an omen! It took many years after the return of the King in 1660 for confidence in the rule of law to be restored and thus it was between the years 1710 to 1770 that the the great hidden relicts of the churches started to reappear and retake their revered positions as holy relics within the church communities

1700 - 1800.

A radiocarbon dating report was commissioned by Chorley St Laurence Historical Society to establish if the bones contained within the reliquary in the church of St. Laurence in the year 2008 dated from between the years 1700 to 1791 when local folklore relates that "the relic of St. Lawrence was returned to the reliquary within the church".

Overview of the results from the radiocarbon dating report June 2008 -:

"the original data from the programme of dating is presented in Appendix 7, which displays the raw age of the sample, and also the calibrated date; the results are explained in Section 2.3. Although the analysis of both bones returned clear and consistent post-medieval dates, the calibrated range is quite broad, from the mid-sixteenth- to mid-nineteenth centuries. Within this range, however, certain dates are statistically more probable than others; it is most likely that the bones are of eighteenth-century date".

1791.

In December 1791 two highly respected Academics Mr. Barritt and Dr. Ferriar arrived at the Church of St. Lawrence to inspect the legendary relict .

The reliquary within the church of St Lawrence 1791.

A manuscript of the antiquary Barritt,

is preserved in Chetham's Library Manchester.

The date of the passage from the manuscript is 1791 -:

“Called at Chorley; after breakfast took a walk to the

church, upon whose mouldering walls are the faint remains of several shields;

one charged with three bears' heads muzzled, another with three boars' heads,

and a third with three standing dishes, most probably the arms of the founders of

the church. The second coat I should suppose was for Barton, a family once of

note in this county; the last is evidently for Standish, a Baronet's family in

the neighbourhood.

In the chancel are mural monuments and funeral trophies to

the memory of several of the Standish family, who have an elegant seat at

Duxbury, and are a branch of the Standishes of Standish, near Wigan.

In a small recess on the south side of the Communion table

are three or four large bones white with age, and secured from further injury

by a door in the recess, which was opened by a boy to give us liberty of

viewing them. They are represented to be human, but plainly appear to belong to

some large quadruped.

My good friend Dr. Ferriar being along with me, without hesitation pronounced one bone in particular to be the uppermost joint in one of the hind limbs of either horse or cow species and that the recess used to contain the bones was clearly an early type of font once used for holy water”. Mr Barritt - December 1791.

1791 - 2008.

However the head of St. Lawrence was not returned to its reliquary within the church as the relic had allegedly been buried with its lawful owners whose line was now extinct.

The legal question of ownership to the relic of St. Lawrence had to be answered "who was the ownership of the relic now with" -:

1. The Church Authorities?

2.The Irish branch of the Standish family?

3.The American branch of the Standish family?

4. The new lords of the Manor of Duxbury descended from Colonel Richard Standish in 1647? (line extinct 1812)

There was NO answer to the legal conundrum and this resulted in the early 1700’s to several bones from some humble animal being displayed in the reliquary of the Church of St. Lawrence in the guise of the original relic of the actual saint.

![]()

1425.

Whose Head did Sir Rowland Standish bring from Normandy to his Manor of Duxbury?

1. St. Lawrence deacon of Rome Martyred on a gridiron in the year 258 and buried in Rome?

2. St. Lawrence O’Toole Archbishop of Dublin buried in Eu, Normandy in the year 1180 ?

![]()

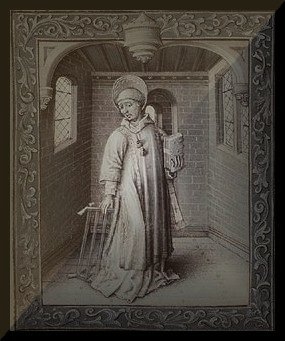

1. St. Lawrence Deacon of Rome - Martyred in the year 258 .

St Lawrence Deacon of Rome

When Archdeacon Sixtus became Bishop of Rome in 257, Lawrence was ordained a deacon and was placed in charge of the administration of Church goods and care for the poor. For this duty, he is regarded as one of the first archivists and treasurers of the Church and was made the patron of librarians.

In the persecutions under Valerian in 258 A.D., numerous priests and deacons were put to death, while Christians belonging to the nobility or the Roman Senate were deprived of their goods and exiled. Pope St Sixtus II was one of the first victims of this persecution, being beheaded on August 6. Lawrence is said to have been martyred on a gridiron.

After the death of Sixtus, the prefect of Rome demanded that Lawrence turn over the riches of the Church. Ambrose is the earliest source for the tale that Lawrence asked for three days to gather together the wealth. Lawrence worked swiftly to distribute as much Church property to the poor as possible, so as to prevent its being seized by the prefect. On the third day, at the head of a small delegation, he presented himself to the prefect, and when ordered to give up the treasures of the Church, he presented the poor, the crippled, the blind and the suffering, and said that these were the true treasures of the Church.

"The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence" by J. León (1758) R.A.B.A.S.F., Madrid.

By tradition, Lawrence was sentenced at San Lorenzo in Miranda, martyred at San Lorenzo in Panisperna, and buried in the Via Tiburtina in the Catacomb of Cyriaca by Hippolytus and Justinus, a presbyter. Tradition holds that Lawrence was burned or "grilled" to death, hence his association with the gridiron.

Lawrence was actually beheaded and not grilled, but the tradition of him being cooked is stronger than what actually occurred. One of the early sources for the martyrdom of Saint Lawrence was the description by Aurelius Prudentius Clemens in his Peristephanon, Hymn II.

The Basilica of San Lorenzo in Panisperna was built over the place of his martyrdom.

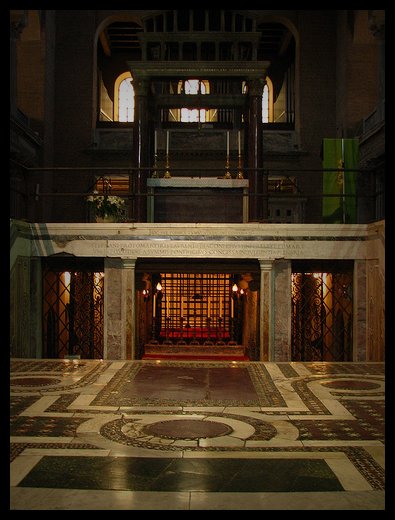

The tomb of St. Lawrence in the Basilica of San Lorenzo.

The gridiron of the martyrdom was placed by Pope Paschal II in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina.

![]()

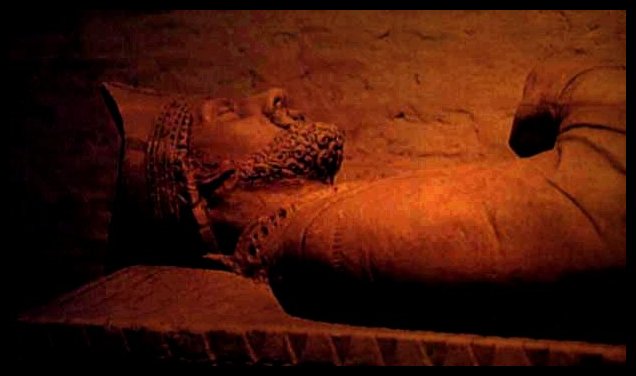

St.Lorcán

Ua Tuathail.

Archbishop Lawrence O’Toole.

In 1180, Lawrence O'Toole, the Archbishop of Dublin and papal legate fell ill at Eu Normandy France on his way to meet King Henry II of England. He subsequently died there. He was beatified in 1186, and canonised in 1225. St Lawrence is the patron saint of the town, and has given his name to the collegiate church (Notre-Dame et Saint-Laurent Eu Normandy France) where part of his reliquariesare preserved.

Notre-Dame et Saint-Laurent where part of St. Lawrence O'Toole reliquaries are preserved.

The County of Eu was created in 996 by

Duke Richard I of Normandy for his illegitimate son Geoffrey, Count of Brionne.

It was a march (buffer zone) protecting

Normandy from invasion from the east.

In 1050, William, Duke of Normandy, the

future William the Conqueror and king of England, married Mathilde, the

daughter of the Count de Flanders at the chapel of the castle in Eu. The chapel

is the only part of this castle which still remains today.

In the 12th century, King Richard I of England, who was also Duke of Normandy, built the city walls

Christ Church Cathedral part of the Anglican Church of Ireland.

Christ Church Cathedral is the mother church for the diocese of Dublin and Glendalough.

It is one of two Protestant cathedrals in Dublin; the other being St. Patrick's Cathedral.

The skull of St Lawrence O'Toole was removed to England in 1442 by a nobleman who fought at Agincourt named Sir Rowland Standish (relation of Myles Standish).The head was interred at the Parish Church of Chorley in England, the church is now named St. Lawrence.

The heart of St Lawrence O'Toole is preserved in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin.

Christ Church Cathedral Dublin, Ireland.

When he was 32 Lawrence O’Toole was elected unanimously Archbishop of Dublin following the death of Archbishop Gregory in 1161. He was the first Irishman to be appointed to the See of this town of Danes and Norwegians; it is notable that his nomination was backed not only by the High King Ruaidri Ua Conchobair, Dermot McMurrough (who had by then been married to Lorcán's sister, Mor) and the community at Glendalough, but also the clergy and population of Dublin itself. He would later endear himself to the people of Dublin with his exertions during a famine which struck the city. He would also play a prominent part in the Irish Church Reform Movement of the 12th century, as well as rebuilding Christ Church Cathedral, several parish churches and emphasising the use of Gregorian Chant.

Archbishop Lawrence O’Toole left Ireland in 1177 to attend the Third Council of the Lateran in Rome, accompanied by five other bishops. From Pope Alexander III he received a Papal Bull, confirming the rights and privileges of the See of Dublin. Alexander also named him as Papal Legate. On his return to Ireland he kept up the pace of reform to such an extent that as many as one hundred and fifty clerics were withdrawn from their offices for various abuses and sent to Rome.

In 1180 he left Ireland for the last time, taking with him a son of Ua Conchobair's as a hostage to Henry. He meant to admonish Henry for incursions against Ua Conchobair, contrary to the Treaty of Windsor. After a stay at the Monastery of Abingdon south of Oxford - necessitated by a closure of the ports - he landed at Le Tréport, Normandy at a cove named after him, Saint-Laurent. He fell ill and was conveyed to St. Victor's Abbey at Eu. Mortally ill, it was suggested that he should make his will, to which he replied: "God knows, I have not a penny under the sun to leave anyone." His last thoughts were of his people in Dublin: "Alas, you poor, foolish people, what will you do now? Who will take care of you in your trouble? Who will help you?"

Lawrence O’Toole was buried in the crypt of the church of Our Lady of Eu and canonized a saint in 1225.Due to the great number of miracles that rapidly occurred either at his tomb or through his intercession, he was canonized only forty-five years after his death.

St Lawrence's skull was brought back to Britain in 1442 by a nobleman who fought at Agincourt named Sir Rowland Standish (relation of Myles Standish). The head was interred at the Parish Church of Chorley in England, the church is now named St. Lawrence's. His heart is preserved in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin.

Story of St Lawrence O'Toole Patron Saint of Dublin Diocese. (Schools Link).

Dublin

Diocese Jubilee Logo

|

St.

Lawrence O'Toole

|

Commentary

The cross stands

for Christ The 2000 stands

for the years |

Reader

1:

We recall Jesus' words Peace I bequeath to you, my own peace

I give you, a peace which the world cannot give this is my gift to you (John14:27) |

Reader

2:

|

Leader:

In the Dublin diocese the Jubilee is being launched on

the feast of Laurence O'Toole who in his own life gave witness to Christ as a

Peace maker, reformer and someone who showed great commitment to the poor. |

Reader

4:

Let Us Pray We Remember how Laurence loved God and gave his life to

serve God's people, especially the people of the Dublin Diocese. We ask

Laurence to pray for us that we will love God and love one another. When Laurence was a boy he was taken away as a hostage

for peace. He was afraid, but he learned to turn to God for help. We ask

Laurence to pray for us that we may not be afraid to be people of peace. Saint Laurence loved the beauty and silence of country

life. He also loved the people of the towns and city. Laurence found time to

pray even though he was so busy. We ask Laurence to help us to realise how

important it is to pray. Laurence was a great friend to the poor, the hungry, the

sick and the lonely. We ask Laurence to pray for us that we will be good

friends to all those in need both at home and throughout the world. Laurence was a leader in the church as Abbot of

Glendalough and Archbishop of Dublin. We ask Laurence to pray for today's

leaders in the church, for John Paul our Pope and Desmond our Archbishop. We

also ask Laurence to pray for us that we may become leaders by our good

example to one another. Laurence tried his best to make peace and prevent war. He

was an ambassador for peace and reconciliation. Let us ask him to pray for

our country and anywhere in the world where there is war. Laurence died in France, a foreign country whose people

treated him with great hospitality and respect. Let us ask Laurence to pray

for us that we may always treat with dignity, those who are different to us

in any way. We especially ask him to pray for all those who are refugees in

our country. Let us pray together as Jesus taught

us- Concluding

Prayer

We

are God's holy and chosen people. God's life and God's Holy Spirit live in

us. We are called to be saints like Laurence O'Toole and all the Saints. May

all the Saints of Ireland pray for us as we prepare for the great jubilee

year 2000. May our country and each one of us be, as Jesus asks us to be, the

light of the world and the salt of earth. May we follow the example of

Laurence O'Toole and be a beacon for peace, reconciliation and justice in our

world. In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

|

Laurence

O'Toole

He was a hostage to Dermot Mac Murrough, Into the tyrant's keeping Rescued from Mac Murrough Now a great man in Dublin, King Rory in his castle, But Laurence rode throughout the land- A hostage in his boyhood: (from Knights of God by Patrick Lynch) |

![]()

Commissioned for the Chorley St Laurence Historical Society by Edwin Fisher - Chairman.

THE BONES OF SAINT LAURENCE,

THE PARISH CHURCH OF CHORLEY ST LAURENCE,

CHORLEY, LANCASHIRE, ENGLAND.

1.Introduction.

In November 2007, Oxford

Archaeology North (OA North) was commissioned by the Chorley St

Laurence Historical Society to organise a programme of radiocarbon dating of the

bones of St Laurence. These bones reside in a wall niche within a chapel of the Parish Church of St Laurence, Chorley,

Lancashire (NGR SD 58285 117750) and, though referred to as 'the bones

of St Laurence', have been identified as elements of the limbs of two ponies

(Stallibrass 1997). The bones of St

Laurence have an interesting, albeit somewhat obscure, history, and it

is clear that the present artefacts are not those relics first brought to

Chorley in the Middle Ages. It was thus hoped that a programme of dating of the

bones might establish more closely the point in time when the extant bones were

deposited, providing a clue as to why, and to where, the 'original' bones of St

Laurence might have been moved. Two of these bones were duly submitted for absolute

dating at the Radiocarbon laboratory at the Scottish Universities Environmental

Research Centre (SUERC).

A Brief Historical Background: documentary

evidence relating to the early history of the Parish Church of Chorley St

Laurence is sparse and, although settlement is documented in 1252, the earliest

reference to a chapel in Chorley dates to 1362. The said chapel may have then

recently-built and at that time had no dedication (Fairer and Brownbill 1911).

The association of Chorley's parish church with St Laurence is likely to date

to the mid-fifteenth century. A document of 1442, now in the British Museum

(Pryor 2008), records a certification by

the vicar of Croston of the donation of the relics of St Laurence by Sir

James Standish of Duxbury. Sir James apparently received the skull of St

Laurence from his brother, Sir Rowland Standish, who had managed to acquire it

following the English victory at Agincourt in 1415 (Edwin Fisher pers com).

Although early records mention the head of St Laurence, eighteenth-century documents refer to the limb bones that comprise the

present bones of St Laurence, and it is likely that the original relics

were transferred to another location prior to that date.

The chequered nature of English political and religious

history means that there are several points in time when it would have been

expedient to hide, protect, or deliberately misrepresent religious relics. In

1552, Edward IV's commissioners confiscated the Parish Church's ornaments,

including a bible (Fairer and Brownbill 1911), although no mention is made of

the seizure of bones or any such religious relics (Edwin Fisher pers com).

Similar acts of vandalism were enacted by Cromwell's hirelings in the

mid-seventeenth century, with the smashing of the church's stained glass and

statues; again, had the bones of St Laurence been available, with all their

Papist connections, no doubt these too would have suffered a similar fate.

2 Radiocarbon

Dating.

2.1 Nature and

condition of the samples: two elements, a right (Sample l/SUERC-17368) and

a left (Sample 2/SUERC 17369) femur, were selected for dating. Although broken in antiquity and a

ittle mouldy, Sample l/SUERC-17368 was well-preserved and dense.

Sample 2/SUERC 17369, as well as being mouldy, was more poorly-preserved, with

considerable degradation of the organic

component of the bone, and exhibiting cracking and surface exfoliation. This

might in part relate to periodic changes of wet and dry conditions

arising from its storage in the chapel wall niche, although it is possible that

this bone had been exposed to weathering prior to incorporation with the bones

of St Laurence. As a result, this bone was extremely brittle, and broke into

two pieces during processing. Whilst neither bone was complete, the slightly

more robust appearance of Sample l/SUERC-17368 and the differential state of preservation

would suggest that the bones derived from different animals.

Overview of the results: the original data from the programme of dating is presented in Appendix

7, which displays the raw age of the sample, and also the calibrated date;

the results are explained in Section 2.3. Although the analysis of both

bones returned clear and consistent post-medieval dates, the calibrated range

is quite broad, from the mid-sixteenth- to mid-nineteenth centuries. Within

this range, however, certain dates are statistically more probable than others;

it is most likely that the bones are of eighteenth-century date.

Discussion and

explanation of the results: the

radiocarbon dating certificates in Appendix 1 show a radiocarbon age,

expressed in years before present (BP: always taken as 1950); that for Sample

l/SUERC-17368 is 230+/-35 BP and that for Sample 2/SUERC 17369 is 190 +/-35

years BP. These raw ages, shown on the accompanying graphs as red peaks

emanating from the y axis, represent a direct measurement of the amount

of radioactive carbon that remains

preserved within the bones. However, due to differences in the level of atmospheric

carbon through history, these raw ages have to be calibrated with reference to

a 'fixed' chronology. This 'fixed' chronology is referred to as a calibration

curve and, on the graph accompanying each certificate in Appendix 7, is represented by the rather irregular line

which descends erratically from the top left hand corner. Calibration

has been achieved by utilising dendrochronology, the study of tree rings. Each

year of a tree's growth is marked by an annual ring, the thickness of which is

determined by the prevailing weather conditions. Over time, a sequence of rings

develops that is unique to a particular period of time within any given region.

Through the recovery of such timbers from archaeological sites, it has been

possible to build up a near-continuous sequence of tree rings stretching back

several thousand years. By radiocarbon dating timbers that have been fitted

into this sequence, it has been possible to

demonstrate that raw radiocarbon dates do not necessarily follow a

linear, chronological pattern, but also to develop a system to calibrate these

raw dates.

The calibrated results

of the radiocarbon determination are shown as the series of black peaks emanating form the x axis

(labelled calibrated date). The calibrated date is achieved by tracing the red

plot of the radiocarbon determination across the graph in order to cross the

blue calibration curve; in theory, the point at which the radiocarbon

determination and the calibration curve

meet provides the calibrated radiocarbon date. The original radiocarbon

determination upon which the calibrated date is based is in effect a range of

dates centred around a mean, and this range is necessarily transferred to the

calibrated date during the process of calibration. This range can be refined by

using a probabilistic methodology to take into account the Gaussian

distribution of the raw radiocarbon determination relative to that of the

calibration curve, to produce the histograms displayed at the base of the

graphs (Bowman 1995). Thus, the overall date range is indicated by the width of

the base of each histogram, with those dates that are most probable indicated

by individual peaks.

An

examination of the calibrated dates for the bones of St Laurence shows that the

attribution of a specific date is a little complex; this is largely caused by

the present state of the calibration curve itself. Rather than following a neat

slope, the calibration curve for much of the post-medieval period is somewhat

erratic, with the result that it is crossed by the raw radiocarbon

determination at several points. There are thus several peaks, rather than a

single one. In theory, the bones could date from the mid-sixteenth century to

the present, although the use of the probabilistic method of calibration means

that there is more chance that the bones belong to certain periods than others.

A sixteenth-century date, whilst possible, is extremely unlikely, and even more

so when it is considered that only one of the bones falls within this age

range. Although there is a reasonable chance that the bones might be

seventeenth-century in date (40.2% in the case of Sample l/SUERC-17368 and

22.1% in the case of Sample 2/SUERC 17369), the fact that the probability for

both bones to be eighteenth-century in date is both higher, and more similar in

terms of percentage, would suggest that the bones are more likely to date to

the eighteenth century. Although the date can shed little light on the fate of

the original bones of St Laurence during the Reformation or the English Civil

War, it does tie in well with the eighteenth-century reference to the bones as

elements of the limb rather than a head (Edwin Fisher pers comm). It is of

interest to note that, had the bones been deposited in the Middle Ages, perhaps

even at the time of Edward IV, due to the shape of the corresponding section of

the calibration curve, it is likely that it would have been possible to gain a

more definitive date.

Dating

convention and recalibration: the sciences of radiocarbon dating and

dendrochronology are constantly developing, to that extent that new calibration

curves are likely to be formulated in the future. It is possible that recalibration

of the raw data in the future may provide a more refined date than it is

presently possible to attribute to the bones. If dates are submitted for

recalibration, it is important to use the standard dating notation, as

indicated below:

Sample

1

|

1520-1960 cal AD (230+/-35 BP) SUERC-17368

|

Sample

2

|

1640-1960 cal AD (190+/-35 BP) SUERC-17369

|

The same form of notation is used when presenting the radiocarbon dates in print.

3. Acknowledgements

OA North would like to thank the Chorley St Laurence Historical Society for commissioning the work and, in particular, Ed Fisher for his liaison and provision of information. The radiocarbon dating was organised by Elizabeth Huckerby of OA North and the dating was undertaken at SUERC under the auspices of Dr Gordon Cook.

4 Bibliography.

Bowman, S, 1995 Radiocarbon

Dating, British Museum Press

Fairer, W, and Brownbill, J, 1911 Chorley, in A History of the County of Lancaster:

Volume 6, 129-149

Pryor, R, 2008 History of Saint Laurence's Church, http://stlaurencechorley.googlepages.com/history

Stallibrass, S, 1997, St Lawrence's Church Chorley Lancashire, "Relic Animal Bones" Durham Environmental Archaeology Report 51/97

![]()